In this series of blogposts, I will document my experience of porting the game that I am currently working on to the jai programming language. It’s currently written in mostly D and some C++ and comes in at exactly 58,620 lines of code (excluding libraries). I’ve planned on doing this for a long time and want to keep some sort of record of my expectations, the journey and the result. And since every self-respecting programmer needs to start a blog at some point - why not share the process with the internet?

Why

You may rightfully ask yourself: Why would anyone port a program of this size to another programming language? Just finish the project and then move on to the new language. In my case it’s for a couple reasons:

- The current setup causes me a lot of grief in day-to-day work

- I have systems in place to help me porting, so I expect porting to go somewhat smoothly

- jai seems way more attractive to me than either C++ or D

And the most important reason: I just feel like it!

Why not C++

Much has been said about the shortcomings of C++, so I’m not going to go into great detail here. In short, C++ has accumulated decades of bad decisions without any mechanism to get rid of them. The standard library is a disaster, (successfully) using other people’s code is comically hard and somehow each new addition to the language always seems to come with a catch. C++ is right in the spot where its shortcomings cause me a lot of pain, but at the same time it’s not bad enough that moving on is a no-brainer. But since it’s also not evolving in a direction I find promising, I don’t expect things to get better and want to leave the C++ ecosystem.

Why not D

When I started working on my game in 2019, all the reasons for leaving C++ were already true, but I wasn’t sure where to go. Nevertheless, I settled on D since the basic pitch seemed reasonable: C++, but without the bad parts1. Unfortunately, it turned out that we disagree on what the bad parts are and that D has various shortcomings that C++ doesn’t.

That said, D definitely has some advantages over C++, like more powerful metaprogramming, no need for headers, no uninitialized values and more. But unfortunately, these upsides are outweighed by the downsides.

After bouncing between the two available D compilers for Windows (dmd and ldc2) for about 4 years, I find the state of D on Windows to resemble something I would expect from a hobby project, or an immature piece of software early in its development, but not from a language with more than 20 years of development behind it. As of now, I wouldn’t recommend anyone to use D for serious projects on Windows. Staying with C++ is the better choice. From the following problems that I have encountered over the years, by far the biggest one is that debug info on Windows is completely broken:

- 90% of times, the

thispointer is missing or wrong - variables on function stacks are often partially or completely missing or wrong

- values of variables are sometimes reported wrong without any other visible issues

- static foreach expansions are not handled well and confuse the debugger

- mixins (D’s macro equivalent) generate debug info in a way that causes the debugger to not find the correct file (so you step through disassembly)

- moving the instruction pointer back to the previous line in visual studio often crashes the program on the next instruction

On the D Language Code Club discord, I was told that “DMD has historically had a lot of issues with the quality of its debug info” and that it’s being worked on, but unfortunately most of the points above apply to both compilers, not just dmd. Aside from debugging, there are other issues and shortcomings, to a significant part in metaprogramming:

- different compiler phases interact in weird ways that lead to surprises in metaprogramming, while generating misleading errors234

- ldc2 is awfully slow to compile5, but sometimes the only choice because dmd has bugs6

- D offers a betterC mode that among other things disables garbage collection. However, when using this mode, the standard library does not compile and meta programming7 is significantly hampered.

- the documentation is lacking

- … and about twenty other increasingly nitpicky issues.

All this is to say: While D is genuinely better at some things than C++, the issues pile up in other places and make working with it very painful. Bad debug info and the de-facto need for garbage collection are dealbreakers, but there’s also the general feeling that the D creators’ vision of what a fixed C++ looks like is just vastly different from mine. Since I want to improve on C++, not just trade its problems for others, D is not the place to stay for me. I have severe trust issues with debuggers now.

Why jai

This leads us to jai8. Jonathan Blow started development on this language in 2014 and has kept the compiler behind closed doors9 until December 2019, where a closed beta began. This closed beta is still ongoing and about two months ago I was invited to it. Jai was born out of frustration over C++ and as opposed to D, it has evolved in a direction that I think could make a meaningful improvement over C++. In my eyes, the most important ones are faster compilation and allowing metaprogramming via unrestricted compile time execution.

It is important to note that we are not talking about 20% faster compilation and a slight increase of what you can do in metaprogramming. We are talking about 10-100x faster compilation and being able to do anything10 during compilation. Especially meta programming in conjunction with a compile-time compiler API has far reaching consequences, like eliminating the need for build systems or enabling complex, non-heuristic custom checks. On top of that, there are other improvements over C++ like better defaults, easier syntax, a more useful standard library, named function parameters11, the context12, using13 and more. I hope for a variety of benefits from porting my game from D to jai:

- Reducing compile times from about 60s right now to under 5s, hopefully around 1s

- having debuggers work

- Replacing build-scripts with jai code

- Catching more errors by introducing custom compilation checks using metaprogramming

- Replacing complex metaprogramming code with simpler, imperative code

- Reducing noise in the code due to various syntax improvements

- Removing duplication that is unavoidable when using multiple languages

Part of the reason this blogpost exist is because I don’t know yet whether these benefits will come to fruition in the manner I hope. Looking back at my initial expectations and checking how much they have been fulfilled will be an interesting exercise.

Why not something else

Ok, so I don’t like D and C++ and jai looks good. But what about all the other languages?

The largest elephant in the room to address is probably Rust. It has gained a lot of momentum and a zealous community, but personally I simply don’t think it gets the tradeoffs right. Its proponents seem to share a strict memory-safety-is-the-only-way mentality, which I can vaguely relate to, given the many vulnerabilities that are attributed to memory safety, but this overlooks other approaches to making safe and high-quality software that are less extreme. For example, I believe a big chunk of these vulnerabilities would not exist if C and C++ (the most prominent “unsafe” languages for sure) simply didn’t have zero-terminated string, initialized values by default, had a proper pointer+length type thus replacing 90% of pointer arithmetic with easily bounds-checkable code, and had established a culture that discouraged the prevalent ad-hoc style of memory management. In addition to this, I think the most important reason we have so many vulnerabilities (and bugs in general) is completely disregarded in the hunt for “safe” code: culturally tolerated and even encouraged complexity14. In conclusion, putting up with Rusts compile times and submitting to the borrow checker seems like an extreme solution that doesn’t address the most important problem, which is a cultural one. Jai on the other hand is extremely concerned with complexity and tries to get the cultural part right.

For other less popular options like for example Zig, all I can say is that while they might have enormous potential, I simply wasn’t totally convinced that they would be the right choice. That doesn’t mean they are bad or anything, but it simply didn’t fully click.

How

In the beginning I hinted at expecting the porting process to go somewhat smoothly (which I’m sure I won’t regret later). The reason for this is that I have two systems in my game that will hopefully be immensely helpful in this endeavor:

- The game records the inputs (HID, loaded files, network, …) of a play-session into a file and replay them later. When replaying, feeding recorded input into the deterministic game loop leads to the exact same state, down to the bit.

- The game hashes game state at various points during execution and saves these hashes to a different file. When replaying, the contents of this file can be used to check that the execution of the replayed session exactly matches the original execution.

There are a couple of nuances to both features, but they are not important for the big picture. Relying on these features, my plan to porting is the following:

- Copy a small piece of code from D or C++ to jai and make it compile.

- Call the new jai code instead of the old D or C++ code.

- Replay a recorded game session.

- If the replay diverged, porting introduced a bug. Fix the bug.

- If the replay didn’t diverge, porting was successful. repeat.

The key questions for how well this approach will work are:

- Do all introduced bugs actually cause the game state to diverge in a noticeable manner?

- Can the code be ported in small enough increments so that knowing a bug exists makes finding the bug itself easier?

The first question depends on how much of the code is covered by state hashing. There are parts of code that need to know if the game is replaying or not, and these parts will internally behave differently and thus can’t be hashed meaningfully. For example, the write-file function just discards any data when replaying, so if porting introduces a bug in writing files, it won’t be noticed by hashing. Luckily, most code does not fall under this category. Initially hashing was only used sparsely in the codebase, in places like physics simulation (which already was super helpful!), but lately I managed to extend this to including hashing the size and capacity of a dynamic array when inserting into it. This means: When a bug causes any insert into a dynamic array to change anywhere in the entire game logic, it will be noticed. Since basically everything uses dynamic arrays in my code, even the minor changes in intermediary behavior of a big and complicated math algorithm should get noticed.

The second question is a classical programming problem: How well decoupled is your code? This is going to be super interesting because I am going to dig up all the accidental complexity in my codebase that I had forgotten about. An obvious problem are templated functions: These can’t be ported straightforwardly because the function definition and call sites have to be in the same compiler for templates to work, unless you manually instantiate the template. There’s quite some amount of templated code in the codebase, but it is relatively isolated to things like containers or serialization, so I hope this doesn’t cause too big of a headache.

Onwards

Are you still here? I’m sorry, this has gotten way too long. Let me reward you with some pretty stats and pictures! First of all, this is the current state of the codebase:

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Language files blank comment code

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

D 27 10201 3104 32396

C++ 4 2343 411 7807

C/C++ Header 1 533 75 1750

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SUM: 32 13077 3590 41953

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Overall, 45701 lines of D and 12919 lines of C++, for a total of 58620 lines. Compile times are the following:

| compiler | loc | debug | debug loc/s | release | release loc/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cl (C++, v19.33.31630) | 12919 | 2.9s | 4,454 | 5.6s | 2,306 |

| ldc2 (D & linking, v1.27.1) | 45701 | 59s | 774 | 317s | 144 |

| total | 58620 | 61.9s | 947 | 322.6s | 182 |

It regularly happens that ldc2 takes 3 minutes in debug mode, because it peaks at around 8GB of RAM, which can easily saturate my 16GB laptop when a browser is open. Release mode is even worse at 11.5GB.

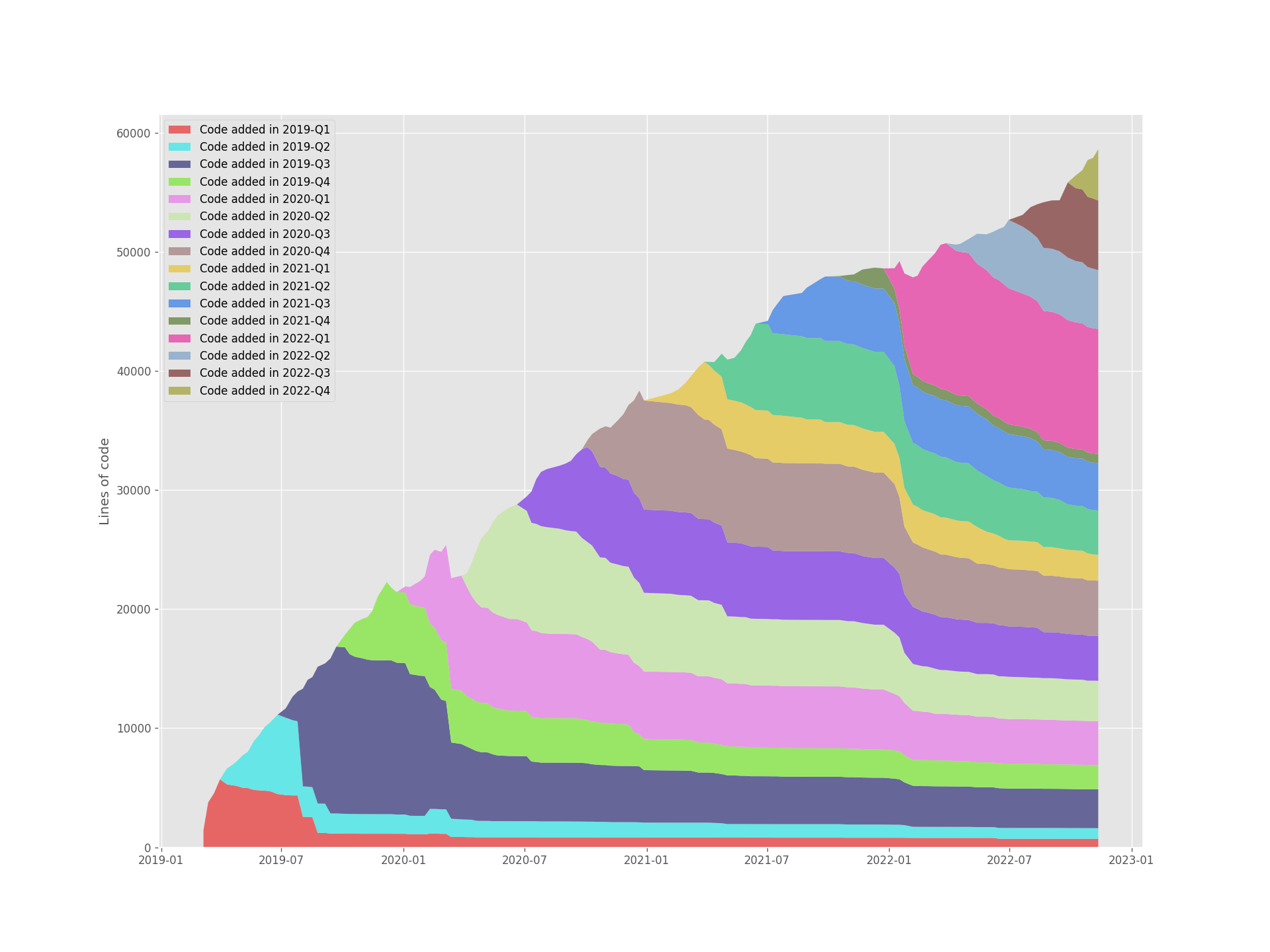

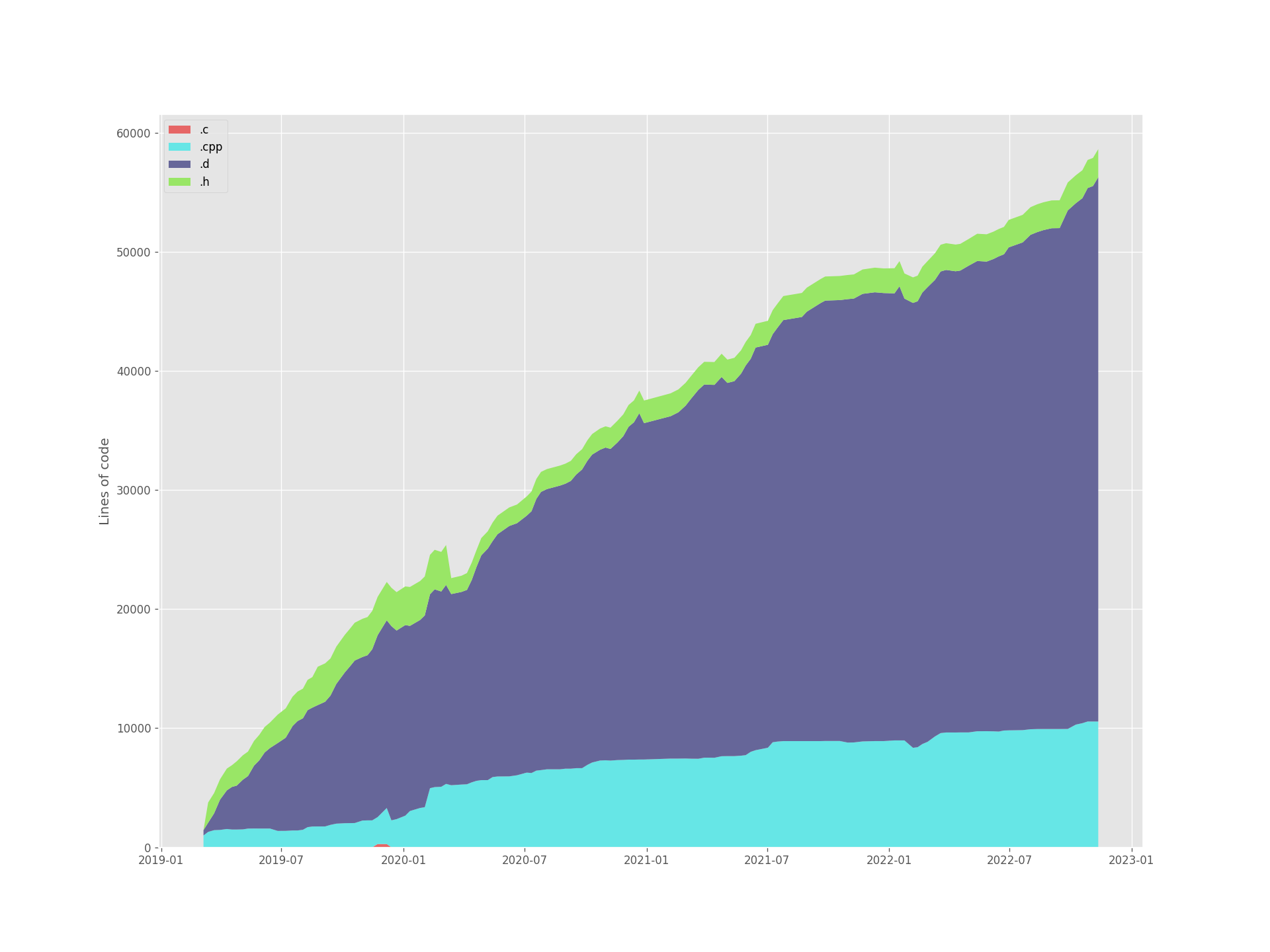

To keep track of the porting progress (and because I love pretty pictures), I generated the following plots of the repository that will be kept up to date as we go along:

If everything goes to plan, then in both graphs all existing color bands should be replaced by new ones. Exciting!

And lastly, let me put numbers on two of the benefits I’m hoping for, so it’s easy to say just how wrong I was in the end:

- I expect this to take 160 hours (one month of 40-hour weeks) of work. I’m horrible at estimating time, but one month seems like a long time.

- I expect the compile time to go from about 1 minute to at most 5s, hopefully around 1s

With that it’s off to the races! See you next time!

-

At least that was my perception of it. ↩︎

-

like order independent declaration in global scopes sometimes breaking with

mixins ↩︎ -

or like namespaced names not resolving in mixins unless you use a special kind of string literal ↩︎

-

or like

static foreachnot being able to insert multipleelse ifs after anif↩︎ -

It takes 1 minute in debug and over 5 minutes in release mode to compile the game. There’s also the issue of ldc2 somehow needing 8GB of RAM in debug and 11.5GB in release mode for compiling a 20MB executable from 2MB of source files, thus causing regular near-death experiences for my laptop. ↩︎

-

I’ve encountered a couple of bugs over the years that stopped my program from building, the latest one being this codegen bug when interfacing with C++. ↩︎

-

Disabling the garbage collector not only disables it for your compiled code, but also for the code executing at compile time. One major way of metaprogramming in D is injecting new code into the program. That code is a string, and those strings need to be concatenated, and string concatenation uses the garbage collector. So … it just doesn’t compile. ↩︎

-

actually, Jon only seems to call it “the language” and has hinted at jai only being a working title ↩︎

-

at least the executable was kept behind closed doors. There were talks, demos and development streams from the very beginning. ↩︎

-

Back in 2014 Jon demonstrated this point by having the program fail to compile unless you reach a certain score in a game that is executed at compile time. ↩︎

-

Why is there a single language without the ability to pass parameters by name in 2022?? Seriously. I find this infuriating. It’s so tedious and error prone if you only want to change the 6th parameter and all others have defaults! Why do they make me pass the defaults to the 5 other parameters in between? ↩︎

-

The context is a data structure that for example lets you modify things like logging functions and allocators in such a way that libraries and leaf code don’t need to know about the changes. ↩︎

-

usingis somewhat like C++’s using namespace, but a lot more versatile. ↩︎ -

This happens everywhere, from encouraging to layer more abstractions instead of fixing underlying issues (“reinvent the wheel”), pulling in everything and the kitchen sink via package managers and perpetuating existing problems by raising software and their creators on an untouchable pedestal (“shoulders of giants”), not to be criticized in their vast wisdom and impossible to improve upon. While well intentioned, this discourages people from even trying. How could you be so arrogant to even assume you could match or outdo the giants? ↩︎